Happy Fourth of July. I am giving this sermon on Sunday, July 2nd. It was originally composed in 2003, and I did my very best to update or clarify some of the statistics, but since I don't have a research assistant (Jess and Dooner offered, but I'm leaving Thursday morning and had to finish this up tonight), this will have to do. If you find any glaringly horrific math errors let me know off--line, and Matthew Gatheringwater, I hope you will e-mail me your phone number!!

-- P.B., hiatusly

[The sermon is preceded by a prayer from Paul's 2nd Letter to the bone-headed Corinthians]

I wanted us to hear from the Apostle Paul this morning because Paul is probably the most famous prisoner in Western religious history, and perhaps in Western literature as well. The Apostle Paul is particularly useful to us this morning because he is a criminal twice over: in Paul’s lifetime in the first decades of the Common Era, he was both a perpetrator of violent oppression, and later a victim of violent oppression.

The interesting thing is, Paul was never arrested or jailed for his early career in torturing and murdering those mostly Jewish citizens of the Roman empire who were considered dangerously misguided for worshiping Jesus of Nazareth as their lord and savior. That behavior was just fine with the Roman authorities! What eventually landed Paul in prison – many times – was his own dramatic conversion to that same religion he had spent so many years brutally suppressing. The definition of “crime,” as we see, is a relative one; history informs us that what constitutes crime is determined by each people in each era. What I am doing right now – a woman daring to preach!-- for instance, could have landed me in the stocks in past centuries in this country. It could land me in jail in some countries today.

As we are sitting here, well over two million men and women – mostly men of color– are living behind bars (that’s the population of the greater Boston area, and an estimated 486 prison inmates per 100,000 U.S. residents) -- up from 411 at yearend 1995. One out of every 140 citizens of the United States woke up this morning in a tiny locked cell, on a cot bolted to the wall, with a toilet in the corner. If they’re very lucky, a stream of light may have come through a high, small window. But most likely not. Another four million Americans are on probation, and about 725,500 are on parole. If this sounds like a shockingly high number of our citizens involved in the criminal justice system as offenders, it is. To have this high of a percentage of the population behind bars is unprecedented in our history and unprecedented on the planet. As of 2003, the United States has the highest rate of incarceration in the world. Mostly due to mandatory sentencing for drug crimes, the number of inmates has quadrupled in American prisons since 1980. In the 1990’s, when the economy was booming, one out of three African-American men between the ages of twenty and twenty-nine was either behind bars or on probation or parole.

I don’t know how many men and women were imprisoned in the first sixty years of the Common Era in the Roman Empire. But at the ending of Paul’s letter to the Romans, he writes this haunting phrase to his community of believers: “Remember my chains.”

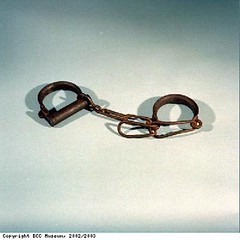

And I do. I remember Paul’s chains, and I think of the shackles that have been placed, and are placed today, on great numbers of human beings whose ideas, beliefs or proclivities were or are in violation of the taboos or social norms of their place and time. In this, the Apostle Paul is in the company of those great authors of prison letters like the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., who wrote from his jail cell in Birmingham, Alabama where he was locked up for civil rights activism, or Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who wrote letters of moral challenge and consolation from his cell in Germany, where he was kept for protesting Nazism, or Alice Paul, the intrepid suffragist of the early 20th century who served three prison terms for her activism. Both King and Bonhoeffer died martyrs, as did Paul.

Please understand. This is not to paint all of our prison population in America with the great brush of liberal pity and delusions of innocent victimhood. Most of our prisoners are not victims. They are not Kings and Bonhoeffers and Saint Pauls or Alice Pauls. They are perpetrators, and they are mostly in prison because they are guilty of something our society has decided is a crime.

You have heard the statistics telling that prisoners are often products of poverty, mental illness

[1] (about 16% of prisoners) and addiction. Our religious convictions call us to note those grim facts, and to care about them. It is also true that most prisoners are possessed of sound enough mind and body to be responsible for their decisions. Our religious convictions call us to note that fact, too. We must hold both of these realities in creative tension. Prisoners are our fellow human beings, and we must remember them, and stretch our own souls enough to be able to acknowledge their basic humanity even when decrying many of their decisions.

When Jesus listed the righteous acts that will create the realm of heaven here on earth, he enumerated these for his community:

"I was hungry and you gave me something to eat. I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink. I was a stranger and you invited me in. I needed clothes and you clothed me. I was sick and you looked after me. I was in prison and you came to visit me.” (Matthew 25:35-37)

So, they may be in chains, but they are still ours to minister to and to keep within the circle of our concern. It is a gospel imperative. We cannot usher in anyone’s idea of the kingdom of heaven if we relinquish 2.1 million fellow citizens to an “out of sight, out of mind” philosophy or dismiss their predicament as being their own literally damned fault. This is a spiritual challenge for us, living in a country that has spent the past twenty years peddling the notion that “soft on crime” is a disastrous recipe for societal chaos and a terrorized population. It is a spiritual challenge for those of us living in a nation whose leaders -- in my memory, at least -- have never dared to express one iota of concern for the imprisoned (if prisoners have come up at election time, they have been used as bogeyman illustrations for candidates’ tough on crime agenda – you will remember Willie Horton). It is certainly a spiritual challenge for those of us who have been victims of crime.

If you prefer not to take that spiritual challenge, consider then the merely practical implications of ignoring Americans in prison: since 1998, about 600,000 people have been released from prison each year – about 1,600 a day. 100,000 of these are released with no community supervision. Practices vary from state to state. In Massachusetts, prisons work with local agencies to find housing and employment for inmates upon their release. In Texas, a prisoner who has served his term gets one hundred bucks and a bus ticket. In Maine, he or she gets up to fifty dollars, some clothes, and a ride home. If there’s no home, he gets a ride to work. If there’s no work, he gets dropped off somewhere – maybe at the state border. In Georgia, it’s twenty-five bucks and a bus ticket.

Where are these people supposed to go? More importantly, who are they supposed to be? If they went into jail or prison a non-violent offender, they’ve been keeping intimate company with violent offenders for some time. They’ve learned violent ways. If they’ve been emotionally neglected, had their basic assumptions about how to function in the world left unchallenged, and left to rot intellectually, they’re not likely to make any better neighbors or co-workers or church members or family members than they did before they went into prison.

Where are they supposed to live? And how? Ex-cons are not eligible to live in public and subsidized housing, even if that’s where their family lives. They’re not eligible to work in a number of professions… including home health aide, firefighter, turnpike employee, bartender, cosmetician or barber.

A total of four million Americans have lost the right to vote because of their incarceration, including one in every seven African American men. (American Radio Works, “Hard Time: Life After Prison,” 2003) In twelve states, this disenfranchisement is permanent; a life sentence no matter what the length of the prison sentence. Not much incentive to participate in social change then, is there? Not much of a sense of personhood.

We cannot underestimate how prisons contrive to strip prisoners of their inherent sense of worth and dignity. A dignified prisoner is a threatening prisoner. By his very presence he shames his jailers, a shame and degradation that already permeates our correctional system at every level. Of course the jailers suffer as well as the jailed: prison guards have the highest rates of heart disease, alcoholism, drug addiction and divorce -- and the shortest life span -- of any state civil servants. (Conover, p.21)

More and more it seems clear that our so-called “correctional” system has no real plan (or desire) to rehabilitate criminals to lead more productive lives outside of prison. “Corrections” began as a system of corporal punishment in early American history (“Before independence, Americans generally flogged, branded or mutilated those felons they did not hang.” – James S. Kunen), and evolved by the late 18thcentury into a punishment more of the mind than the body. The Quakers, beginning with William Penn’s colonial government in Pennsylvania, aimed through the incarceration of criminals to prevent further harm to citizens and to encourage prisoners to penitent reflection, hence the term “penitentiary.” The hope was that the prisoner would truly reform before returning to society. Of course, this was an ideal that was seldom met, or even sincerely sought. The history of incarceration in America is an appalling litany of human rights violations.

[2]I have sat through presentations by prison administrators during prison chaplaincy training (right near here at the Delaware County Correctional Institute in Media), and seen self-congratulatory videos describing “programs” that are intended to ease my sentimental religious conscience about the brutality of life behind bars. These glossy productions are intentionally misleading; disturbingly so. My work inside prisons and as a pen pal to inmates causes me to doubt that there is any greater purpose to most modern American prisons than for both jailers and the jailed to simply endure the passage of time, (“A life sentence in eight-hour shifts,” said one guard about his own professional life) and to make money for the corrections industry.

Yes, corrections in America is

an industry. The construction of prisons is expensive, and private contractors make huge profits building them for the government. Prisoners are consumers, too. They need food (over six millions meals a day) and medical care, they need shaving supplies and uniforms. They need a telephone company to provide them phone service so they can call home or their lawyers. And prisons needs all kinds of products: equipment for the rec. room, surveillance equipment, razor wire, and terrific gizmos like the “B.O.S.S. chair” – the Body Orifice Security Scanner that sells for $5,000 “On its web site, the American Correctional Association points to the $50 billion spent each year to run the nation’s prisons and jails. And it warns companies, ‘Don’t miss out on this prime revenue-generating opportunity!’” (from American Radio Works,“Corrections, Inc.", 2003)

Let me tell you how ethically troubling the corrections system is in our country, in case you never considered, as I did not, that keeping more people in prisons for longer sentences is good business for corporate America:

The American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) is an organization founded in the 1970’s whose stated mission is to “promote free markets, small government, state’s rights and privatization.’ More than a third of the nation’s lawmakers belong to ALEC, whose members meet at corporate-sponsored conferences where they write model legislation and then take those “model” bills home and try to make them state law. Among the corporate sponsors of ALEC conferences are Turner, a construction giant and the nation’s number one builder of prisons, and Wackenhut Corrections, a private prison corporation. (The keynote in 2002 was Jeb Bush, and they gave Zell Miller the “Thomas Jefferson Freedom Award.” That should provide some helpful context. )

The result, of course, is corporate-sponsored legislation, including legislation on sentencing of criminals. I am sure it will not surprise you to also learn that Corrections Corporation of America, which dominates the private prison business (building and running prisons in twenty-one states and Puerto Rico), pays $2,000 a year for a seat on ALEC’s Criminal Justice Task Force. The panel writes the group’s “model” bills on crime and punishment. And I doubt if it will surprise you to learn that the Corrections Corporation of America has pushed a tough-on-crime agenda an influenced legislation on mandatory minimum sentences, and Three-Strikes laws. This is all very good business for those who build and run prisons.

[3] The absolutely appalling conflict of interest here has not yet come to the attention of most Americans, who have been well trained to think of convicts of those who deserve to live behind bars for as long as a judge sees fit to put them there.

(Now you know. And I hope that you will feel empowered to do something about it, particularly around sentencing laws in the state of Pennsylvania. Ask yourselves who stands to profit from incarcerating non-violent criminals. Find out where those released from Delaware go, and those released from Graterford.)

Some time ago, I visited England and went on a tour of a magnificent castle. The first stop on the tour was the dungeon. Not a dungeon, but the dungeon – no home of the wealthy and powerful was complete with a dungeon! The dungeons were set far enough away from the great halls and ballrooms so the ladies and gentlemen of the manor wouldn’t be troubled by the tormented screaming and begging of the damned. I almost cannot catch my breath describing it: the dank, sweaty walls, the unforgiving earthen floor, the darkness, and the smell of fear that remained in that space across hundreds of years. Now a tourist attraction, you understand.

There were shackles on the wall; rusty and well used, where prisoners were hung for days before they died of thirst or injuries. Worst of all, and one of the worse things I have ever seen, was a small hole in the floor covered by an iron grate. The hole was so small that a man would have to curl up to fit into it, and that’s just what it was used for. A prisoner would be shackled in the fetal position and put in the hole, and left to die of madness or physical agony. Usually the first preceded the other.

What was this special torture device called? The

oubliette, taken from the French verb

oublier, to forget.

I have no doubt that some of the men left to perish in the

oubliette were truly dangerous and unrepentant criminals. But I ask you to consider when, if ever, such punishment is the appropriate action of a civilized society or people. I ask you to remember this morning those often forgotten men and women who, although freer in body than the tormented occupant of the oubliette, are often no less confined in intellect and possibility than those tortured souls who ended their lives in the dungeons and oubliettes of past, horrifically unenlightened societies.

Finally, I ask you to hear these words written by the criminal, the prisoner, the apostle, the martyr and the saint Paul, who in his letter to the Romans wrote, “For I am persuaded that neither death nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor powers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor height, nor depth, nor any other creature, shall be able to separate us from the love of God. . . ”

I consider this one of the most beautiful Universalist statements ever uttered. This is our good news. It is not easy news, but it is our news. [

P.Bangers, I know you know that this reading concludes, "the love of God which is in Jesus Christ our Lord," but let's just let it go this once, shall we? This congregation has a hard enough time when you just mention the Jeez, okay?]

For the love of God and the love of humanity, remember them. Include them in your thoughts and prayers for a reconciled world, and in your work for justice, and know that our claim to affirm the dignity of all peoples is tied to their fate. In the words of the beautiful hymn, "In prison cell and dungeon vile, our thoughts to them are winging…"

So may it be, and may we have the courage to make it so. Amen, and amen.

NewJack: Guarding Sing Sing, Ted Conover, Random House, 2000.

[1] My statistics this morning were gathered in 2001 by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the Urban Institute, The Sentencing Project, and The Center for Law and Social Policy.

[2] For a fuller discussion of this history, I encourage you to read Ted Conover’s book NewJack: Guarding Sing Sing, pp 172-209.

[3] I got this information and many direct quotes about ALEC and CCA from “Corrections, Inc